UBU ROI

by Alfred Jarry

Adapted from a translation by Sherry C. M. Lindquist

Original Musical Composition by Evan Chen

Stage and Technical Director, James Rossow

Artistic Director, Michael Schwabe

Producer Director, Lawrence J. Basgall

|

UBU ROI

by Alfred Jarry

Adapted from a translation by Sherry C. M. Lindquist

Original Musical Composition by Evan Chen

Stage and Technical Director, James Rossow

Artistic Director, Michael Schwabe

Producer Director, Lawrence J. Basgall

|

"Over the last 100 years, many productions have sought to reproduce the exuberance and outrage of Jarry's work, but few, I suspect, have got it down as well as the vivid, imaginative puppet edition mounted by Hystopolis." Richard Christiansen, Chief Critic, Chicago Tribune/March 1996

|

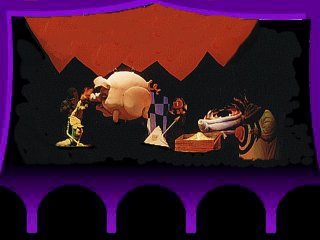

In 1888, at the age of 15, Alfred Jarry helped usher in the twentieth-century's avant-garde movement with this comically serious absurdist work. Originally staged as a puppet show by its author, its live theatrical premiere eight years later in a Paris production became an international sensation. UBU ROI's nihilistic exploration of absolute tyranny is given an astounding new production complete with comissioned translation and musical score by the master theater makers and puppeteers of the Chicago-based Hystopolis Productions.

Jarry's "king" has never been so deliciously stupid, indolent and grotesque. His wife has never reached such heights of farcical malevolence as in the wildly imaginative, bawdy and outrageous production.

Following a two-month run in Chicago, Hystopolis presented its acclaimed UBU ROI to New York City for an 8-performance run in September 1996 to open The Jim Henson Foundation's International Festival Of Puppet Theater.

|

Nuts & Bolts: A production for adult audiences, played in one hour and fifteen minutes, Ubu Roi tours with a group of 7 performers and a staff of 2; best set in houses up to 700 seats. Minimum 12 hour load-in. Proscenium stage. Multiple-performance engagements encouraged. Meet the artists events, lectures, workshops and master-classes are offered.

About the Play Translator's Note: Sherry C.M. Lindquist

Ubu Roi, which premiered at the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre in Paris on December 10, 1896, was nominally directed by the young Symbolist director Aurélien Lugné-Poe, but it was surely orchestrated by its stage manager and playwright, Alfred Jarry. The sets were designed and painted by a now famous group of Symbolist artists "the Nabis" including Srusier, Bonnard, Vuillard, Toulouse-Lautrec and Ranson. The play was a sensation, so controversial that poet William Butler Yeats called Jarry a "savage God."

|

Ubu Roi is notorious for its first word, merdre, which the original Parisian audience recognized as merde, meaning "shit." Legend has it that this initial obscenity shocked the bourgeois audience into outrage and that it took fully fifteen minutes to restore order so that the play could continue. However, it is worth noting that much of the first audience of Ubu Roi was a self-selected group of literati whom Jarry had courted by publishing theoretical articles about theater in Parisian journals. The nonsensical alteration of merde, which nevertheless did not detract from its recognizability, seemed intended to confuse and disorient the hearer; apparently it was a ruse particularly offensive to the savvy nineteenth-century theatergoer. In one word, Jarry managed to offend the sensibilities of his audience and slight their intelligence and it was this combination of injury and insult which proved explosive. Merdre, of course, was just the beginning.

Ubu Roi flouted all manner of linguistic and theatrical convention. Jarry vehemently opposed the popular theater of his day which tended to revolve around the personalities of celebrated actors. He thought that drastic action was needed to restore the theater to a serious art form. He went so far as to call the actor an "object which uselessly encumbers the stage." Actors, he maintained, should "dare to depersonalize themselves voluntarily" in favor of the characters written by the playwright. To ensure this Jarry went so far as to propose that actors wear masks and speak in a "special voice, the voice of the role." This caused some consternation on the parts of the actors who played in the first production. Firmin Gémier, who played the first Ubu, was known to resent the heavy mask and cardboard stomach in which Jarry encased him.

|

Furthermore, Jarry directed the actors to simulate the unnatural jerky movements of marionettes, and this further discomfited the audience. In his address to the crowd preceding the first performance of Ubu Roi, Jarry even referred to the actors as "man-sized marionettes." Indeed, Jarry never abandoned his youthful fascination with puppetry, which he incorporated into his theories of the theater. Jarry insisted by way of his subtitle that the first production of Ubuwas "restored in its entirety as it was performed by the marionettes of the Thtre des Phynance in 1888." Ubu Roi was based on, as he put it, "a schoolboy's caricature of one of his teachers who represented for him everything in the world that is grotesque."

Félix Hébert was Jarry's large, dim, unfortunate physics teacher who was the habitual butt of generations of savage schoolboy derision and subject of numerous stories, spoofs and puppet plays. Jarry, it seems, was his most relentless detractor. Jarry crafted Ubu out of the rich mythology built around this quasi-fictional character. In fact, two of his former cohorts and co-creators, Charles and Henri Morin, charged that Jarry's only original contribution was to come up with the name "Ubu." Such charges are misguided, however. Jarry was the only one who had the notion and the temerity to elevate the juvenile works to the status of art. Like the Symbolists, Jarry believed art should strive to be universal, eternal, general, rather than historical, topical, specific. The play was set in Poland, "that is to say, nowhere." Furthermore, Ubu was not Félix Hébert, but an archetypal character modeled on Shakespeare's Macbeth. Despite Jarry's protestations of political neutrality, many have applied Ubu Roi as a critique of governmental tyranny; this accounts for the play's recent popularity in Romania. That Jarry's contemporaries associated the play with the ideas of anarchists responsible for a rash of terrorist bombings on the streets of Paris fueled the outrage of his critics. Jarry, however, insisted that Ubu was merely the reflection of our worst selves, composed of "eternal human imbecility, eternal lust, eternal gluttony, the vileness of instinct magnified into tyranny; of the sense of decency, the virtues, the patriotism and the ideals peculiar to those who have just eaten their fill." Furthermore, "it is not surprising that the public should have been aghast at the sight of its ignoble other self, which it had never before been shown completely." According to Jarry, the public "resented [Ubu Roi] because they understood it only too well, whatever they may say."

|

Ubu Roi today is far less likely to engender the kind of resentment and outrage which was the aftermath of the 1896 performance. Part of the reason is that Jarry's uses of abstraction and absurdity, so confounding to a nineteenth-century audience, have become familiar characteristics of twentieth-century art, literature and theater. In fact, Dadaism, Futurism, Surrealism, and the Theater of the Absurd all claim Jarry as forebear or muse. Even without the initial shock, Jarry's blend of horror and farce continues to be unsettling, hilarious, and resonant for us.

Richard Christiansen, the chief theater critic of the Chicago Tribune, writes that "over the last 100 years, many productions have sought to reproduce the exuberance and the outrage of Jarry's original work, but few "have got it down as well as the vivid, imaginative puppet edition mounted by Hystopolis." I admire their work so much that I have even allowed them some freedom with my translation. I must warn you, however, that as you've probably discerned, the show contains profanity and imagery that some viewers may find disturbing. It is not suitable for children. It is to the great credit of Edison Theater that they have brought us a work of theater that is at once historically significant and avant garde. Hystopolis and the Edison theater join Jarry in addressing an audience comprised of what he described as "intelligent souls agreed to become Poles for a few hours" or more precisely, one hour and fifteen minutes without an intermission.

Mail to: RedRaven@ArtOfThePuppet.com

Copyright © 2001 T.Dwyer, Michael Schwabe, Larry Basgall